The Well Tempered Cellist – Part 3

Thinking Back to Front

“Let the spine light up your fingertips.“

– Patrick Macdonald

“A wheel needs a central point of contact, an axis, in order to turn and spin. One never loses touch with one’s central point – the spine – as one moves through life. But society today has lost that core. It has no idea where it is going.”

– Svami Purna

“Stay back, aim up and let ‘it’ be done for you,” are the words of the late and great teacher in the Alexander Technique, Patrick Macdonald. What does it mean to stay back and aim up so that ‘it’ can happen?

Opening the way for ‘it’ to happen implies a certain quality of attention. Great musicians of all persuasionsóAfrican drummers, tango violinists, jazz pianists, fado singers, and inspired cellists tooótake themselves and their listeners up where the music is. Their energies, when flowing freely, create a cybernetic loop. Energy begets energy and before long the entire performance space and all the people in it are buzzing, charged with that indefinable ‘something’ that makes a performance unforgettable.

How can we open the way for this ‘it’ which takes us up and frees us to communicate through the music? There are many paths; I just happened to discover one of them through the Alexander Technique, a practical way of working in harmony with, instead of against, ourselves.

Most of us have little reason to question our habits of movement. We move automatically, as we learned to do many years ago. Sometimes pain brings us to the wall; sometimes a pattern of going wrong time and time again will do so. Awareness of our habits begins with the question: what are we doing, how and why? As our understanding grows and deepens, we begin to respect ‘it’–that moving force within us which we cannot directly control but which, when the conditions are created, allows for ease and freedom in movement. There are coordinating mechanisms present in the brain, inner ear and eye which help us to balance and to counteract the downward force of gravity as we move, and even as we sit with our cellos. Becoming conscious of how not to interfere with these balancing mechanisms is the name of the game

Alexander’s patient experiments in front of a mirror as he looked for the root causes of his vocal hoarseness bore fruit for all of us. He discovered that he interfered with his breathing, his speech, and his overall coordination by the habits he had acquired. His neck tightened in anticipation of speaking, his head pulled back and down into his spine, and his entire back narrowed and arched forward as he threw himself into the act of reciting on stage. Not a pretty picture. He called it his ‘misdirection of use’; in other words, his intentions caused his tensions. How did he dig himself out of this deep hole? It is a great detective story, one worth reading about in his book called The Use of the Self. There is space here only to outline some of the fundamental principles.

In this exploration of movement and habit, as the Chinese saying has it, a great journey begins with a single step. Your orientation has to change. Awareness of your neck, head and back becomes primary whether you are at rest or in movement. What is out there in front of you, waiting to be done, becomes secondary.

In our fast-paced Western culture, most of us are go-getters. We don’t stop to consider what we are doing to move. We just go for what we wantónow and in the next moment. Alexander named this habit ‘end-gaining’, and it is the first of two important concepts in his work. Beyond the personal, there are the philosophical implications of acting without consideration. As we mis-use the energy in our own bodies, we waste the same in the world around us. To alter this attitude is an enormous challenge for us, as it was for Alexander.

The second and related concept is called ‘the means-whereby’, the alternative to end-gaining. The means-whereby is the key to intelligent movement. Alexander’s directions for the means-whereby are:

- to let the neck be free; in other words to stop tightening the muscles of the neck

- to let the head go forward and up; i.e. to stop pulling the head back and down into the spine.

- to let the back lengthen and widen; i.e. to stop the downward pull on the spine and to stop narrowing and arching the back forward.

These directions activate what Alexander called the Primary Control –the coordinating mechanisms present in the brain, eye and ear which balance the whole of us in movement and orient us upward. These directions invite us not to interfere with movement; they ask of us the patience and the humility to stop, to wait, and to allow these mechanisms to function. Alexander is describing here a reasoned response, not an immediate reaction.

The back and spine could be called our ‘Central Reserve Bank.’ The spine contains the nerve channels for the entire nervous system. The back possesses the largest and most powerful system of musculature designed to mobilize our limbs and get us around. We don’t swing from trees any longer but we still have miles to go before we sleep. Our work as cellists is complex. We do not need to contract opposing sets of muscles, as is so often the case. When the back provides the power to the arms and legs through the employment of the Primary Control, the fingers have the easiest time fulfilling their demanding role –delivering the notes.

Alexander’s directions– to let the neck be free, to let the head go forward and up, so that the back can lengthen and widenóspecify that before the muscles of the back come into play, there must be a freeing of the neck muscles, allowing the head to go forward and up. Why is this sequence important?

When the neck muscles tighten, the resulting tension pulls the head downwards into the spine, compromising the freedom of the spine and tensing the very back muscles we need to use in our activities as cellists. It starts with the neck and follows on from there, a reproducible sequence in all creatures with a spine. If you have ever wondered why a mother cat picks up her kittens from the neck, now you know. No vertebrate can use their limbs when their neck is immobilized.

One important caveat here: In his books, Alexander specifies that his directions are to prevent this wrong sequence of events described above from happening. One cannot ‘do’ the directions but can only allow them to come into play. Trying to do the right thing is counterproductive. The right thing does itself.

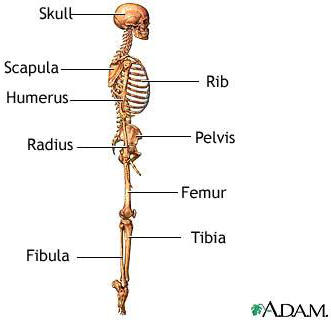

Let’s take a look below at two aspects of the human body: our skeletal construction and the web of muscles connecting the head, neck and back:

Fig. 1: Skeleton (rear view)

Fig. 2: Skeleton (lateral view)

You might, upon closer examination of the human skeleton in the above pictures, wonder where the neck is, and you would be right. Our basic skeletal construction is skull and jaw, spine, ribs, pelvis and limbs. The neck consists of a web of interconnected muscles which fills the space between the top of the ribs and the skull.

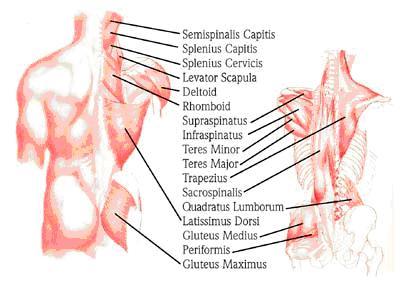

Below are three representations of the interconnected musculature of the head, neck, and back.

How important it is to understand the relatedness of our construction when relearning to use the back properly. It is not enough to speak of the use of the back. We attend to the whole relationship of the neck/head/back, including the pelvis, to allow for the lengthening of the spine. The next article in this series will address this aspect in more detail.

Fig. 3: The musculature of the back and related areas of the neck and shoulders.

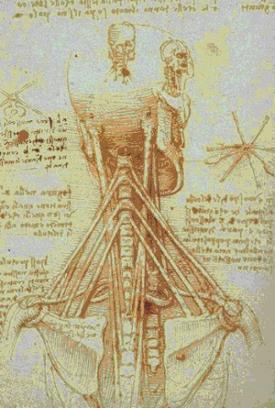

Fig. 4: Artist’s representation of the same

Fig. 5: Leonardo da Vinci’s representation

Allowing for the release in the neck muscles means that the head can balance freely atop the spine. Once the considerable weight of the head (4+ kg.) is releasing upwards and properly balancing, then the spongy, springy discs of the spine can assume their role in cushioning the vertebrae. Without the unnecessary force of compression from an improperly balanced head, the musculature of the back can come into play as neededóin Alexander’s words, the back lengthening and widening. The legs become free for standing, walking or running, the arms for lifting, pulling or pushingóall in all, ideal conditions for mobility. It is worth remembering that Alexander solved his vocal problems by attending to his entire self, not just parts of himself.

What does the above mean for us cellists? The muscle mass of the back is perfectly formed to counterbalance the work of the arms and hands which takes place in front of us. As we lift a cello, the weight of the instrument has to be borne primarily by the back and not the muscles of the neck, shoulders and arms. As we move the hand along the fingerboard and the bow across the string, these same muscles provide the power and energy to the smaller muscles which have faster and more complex movements to negotiate.

This work asks of us a certain kind of practice: to return to a state of quiet and to remember the directions. Given time, the work becomes less strange and less difficult –-to let the neck be free, to let the head go forward and up, and to allow the back to lengthen and widen is to enter a state of grace and freedom. I suggest to my musician pupils the parallel between the Primary Control and their sense of pitch when playing. Both involve ‘listening’ in the present moment and neither is automatic. Pablo Casals called good intonation ‘a matter of conscience.’ Awareness of the Primary Control could be called a ‘matter of consciousness.’

My work with musicians and students always begins and ends with simple procedures to encourage awareness of the back and the upward flow of energy along the spineówork lying down, against the wall or a door corner, against a chair and finally standing independently once they have internalised this awareness. This work builds an inner strength as well as a reserve of energy. The stimulus to react to what is in front of us is hugely powerful. To remember ourselves quietly– first of all– from the ‘back to the front’ is what makes us conscious human beings capable of intelligent action.

Additional Resources

Latest News

- The Use of the Legs in Standing and Sitting May 9, 2020

- An Interview with Selma May 9, 2020

Copyright © 2024 The Well-Tempered Musician. All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy | Website Maintained by Nebulas Website Design.