Well Tempered Cellist – Part 4

Sitting Pretty

In the catbird seat – Said to derive from the habit of the catbird of sitting on the highest point it can find to deliver its song, thus suggesting an effortless superiority.

“There is no such thing as a right position, but there is such a thing as a right direction.”

– FM Alexander

In this next part it is worth taking a look at our starting point as cellists– how we sit in a chair. As a child I was fascinated by all the manuals that explained cello technique, beginning with pictures of the right way to sit with the cello. Small bodies, tall bodies, long arms, short arms– all eventualities were explained by relating the person to points on the instrument. What happens if you don’t look like the picture? Don’t worry, follow the instructions anyway! It wasn’t until I encountered the Alexander Technique that the ‘how’ of sitting came into clear focus.

What is the fuss about sitting in a chair? In the world of the plush sofa, easy chair and computer, our simplest movements have lost their vitality. In the act of sitting, Alexander observed that most of us in the ‘civilised’ world violate the fundamental principles of coordinated movement. We tighten the neck, pull the head back and down, shortening and contracting through the spine, and using our ‘bottom’ to find the chair.

Figure 1: Pulling the head back and contracting the spine to sit

(from The Alexander Technique by Wilfred Barlow. p 18) .

Figure 2: The same mis-use to sit.

The challenge of sitting well begins not on the chair but before we ever get there. It is to learn, as we initiate movement towards the chair, not to tighten the neck, first and foremost. Then to allow for the balance of the head (4.5 ñ 5 kg) on top of the spine, to allow for the spine to lengthen and the back to widen, helping the pelvis to find its dynamic equilibrium as it finally touches the chair. The largest muscle mass of the back, the erector spinae, which is divided into three longitudinal columns, assists us, permitting a freedom and lightness of movement sometimes referred to as the ‘anti-gravity response.’ We literally can learn to go up against gravity as we sit down. To experience this for the first time is startling. It doesn’t seem possible to float upwards into a chair, but it can happen.

Once seated, our feet permit a transfer of weight through the body as our arms move, stabilizing our entire corpus. Grounding, or using the floor as a stable point from which to shift our balance, is a crucial element of sitting. Have you seen cellists play entire performances with their heels raised up from the ground, the tension present in the back of the legs invading the entire body right up to the face? Learning to release the feet, allowing them to ‘take hold’ of the floor, offers a fundamental sense of place and surety to the player and eliminates the need for excessive movement.

In the Alexander Technique, the chair is both a friend and enemy. It offers us an easy opportunity to examine a habit — we sit down and stand up hundreds of times a day. And yet as anyone who has had lessons can testify, the chair shows us how painfully captive we are to our habits of tightening and shortening as we prepare to move.

Working with this simple activity of sitting down, we also encounter something quite new. How to quiet the mind and not prepare to ‘sit down’. Why should this matter as a first step? If you recall from Part 2 of this series, the very thought of an action sets in motion our usual preparation– our habit of tightening the neck, pulling the head downwards into the spine, shortening and contracting through the spine, with its accompanying tensions in the limbs, unnecessary and counterproductive. So the adventure involves a new way of thinking, of learning what not to do instead of what to do. Such a simple activity allows us to see how we react moment by moment, from the first thought of sitting down to our final destination, the chair. Learning to respond without tightening and ‘losing one’s back’ requires consciousness of the harmful things we do. It takes practice, a lifetime of it.

Let’s take a closer look at five major areas of ourselves, all interconnected, which are key to the free use of ourselves at the cello:

The Neck and Head

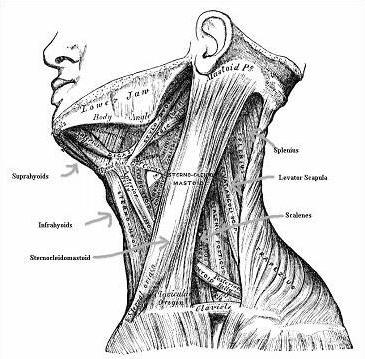

Alexander noted in his experiments with his vocal production that tension originates in the neck, and travels from there throughout the organism. Why the neck? Creatures with spines and heads have important reflexes in the neck, the key juncture between the head and the body. Extraordinarily complex and powerful groups of muscles which connect the head to the body travel through the neck region (see Fig. 2 and 3 below.) Our righting reflexes operate through this region to re-orient the head when we lose our balance, and the transmission of spinal cord impulses which originate in the brain pass through the neck area into the torso and limbs. Your neck tells your storyÖare you easy, tense, anxious, a pain in the neck?

Figure 3: Muscles of the Neck and Jaw.

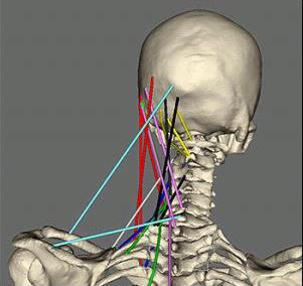

Figure 4: Points of connection of the skull to the spine and torso through the neck region.

To give you an idea of how the head balances on top of the spine, put the tip of your two middle fingers, one each, in the soft area under each ear. Tighten the neck as hard as you can and try to nod your head. Then release the neck completely and allow the head to nod forward and back on the along the axis formed by your fingers. The difference in mobility is easy to detect. In sitting, as well as playing, it is only necessary to remember that any tension beyond what is required to balance the head is damaging to free and efficient movement. And neck tension is unfortunately what we cellists do best, along with our other string playing colleagues!

Figure 5: Neck tension engenders a downward force throughout the body.

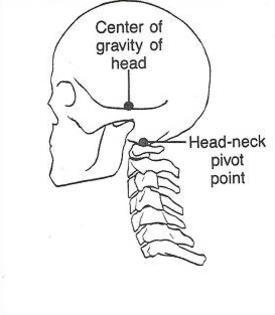

Once we bring quiet to the neck region the head finds its balance on its own. It tends to balance slightly forward of its balance point on the spine (because the center of gravity of the head is forward of the spine) and of course always up of the spine, never pulled back and downwards. Notice from the drawing below that the resting point of the skull on top of the spine is roughly behind and well in from the nose, and much higher up than one would suspect.

Figure 6: Center of Gravity of the Head

Here is one of my favourite pictures (Figure 7) of a free neck and wonderful poise of the headÖforget the cigarette!

Figure 7: Emanuel Feuermann (Courtesy of www.celloclassics.com)

The Pelvis

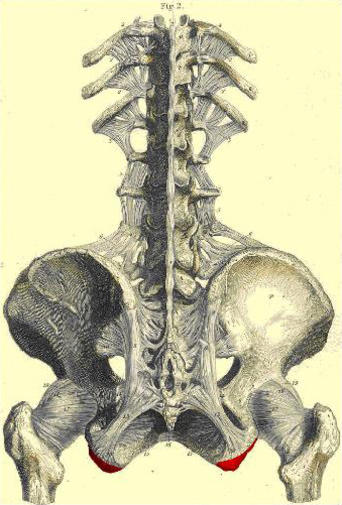

At the other end of the spine is the pelvis, that wonderful butterfly-shaped ‘basin’ whose rocker-shaped bones, the ischial tuberosities (colored in red), allow us to balance on a chair and move forward and back, side to side (see Fig. 8 below).

Figure 8: The Human Pelvis

The pelvis is a highly-developed marvel of our anatomy, stabilizing us while we do complex things with our hands. It anchors the lower, powerful part of the spine, and is the ‘other end’ of us, literally the seat of our being. If the head allows us to look out into the world and dream, the pelvis anchors us towards earth. We even have what is called the ‘pelvic floor,’ a complex web of ligaments and muscles shaped like a cradle which contains us so that our organs do not spill out.

Any sideways twist or rotation of the pelvis relative to the spine can affect the freedom of the whole body while playing. Looking at a cellist from behind sometimes reveals a pelvis pulled up or turned to one side, because the instrument crosses us from right to left as we sit. Not only the torso can be twisted but even the pelvic structures can become fixed or unbalanced, distorting the movement path of the arms.

Slip your hands, palms facing up, under your bottom and rock forward and back to find your ‘sitting’ bones (highlighted in red in the picture above). To balance well on the pelvic bones, we have to look at the top end of usówhat is happening with the head? Is it bearing itself forward and up of the spine so that the pelvis is neither shoved forward, backward or twisted to one side? So our top and bottom form a dynamic relationship. In all my years of learning to play the cello, no teacher ever made this connection for me. I learned it through working with the Alexander Technique.

The Spine and Back

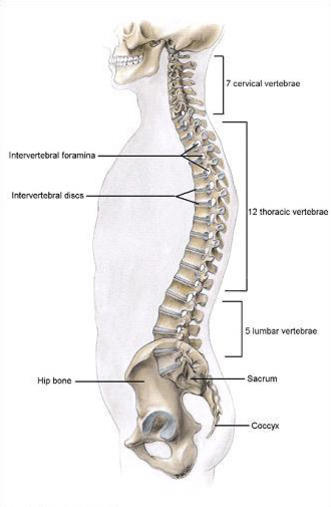

The spine makes us who we are as movers and shakers. Without its spring, without its curves, and without its power we could not be athletes, dancers, acrobats or for that matter musicians. The spine is extraordinarily long relative to our width and is, of course, weightbearing. The top of the spine is as shown below. You can find it by placing your two middle fingers in the dip along the rear ridge of your skull. The bottom of the spine is roughly opposite the pubic bone. Its top is higher and its base lower than one would imagine.

Figure 9: The Human Spine

The ability of the spine to move in so many ways while providing both strength and flexibility has to do with its construction. The curvatures of the spine at both the neck and lower back increase its ability to bear weight. Imagine a thin stick balanced on one end. Press down on it with your palm, forming one sideways curve–the resistance is minimal and it could snap. Put one curve in opposition to another, however, as we have in our spine, and the upward force counteracting your hand is not only stronger but also increases the load-bearing capacity. We carry heavy heads atop our spines. The spring in the spine allows us to bear that weight and more. Abnormal curves such as are present in lordosis (exaggerated lower back curve) weaken the spine.

Witness the poise of this African woman bearing more than we would think possibleÖ

Figure 10: Head in Balance

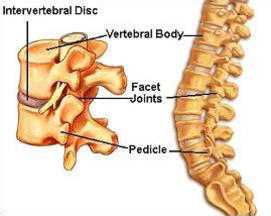

A closer look at the spine (see Fig 10) reveals that the intervertebral disks, made of spongy cartilage that cushions each segment of the spine, allow for movement without the damaging impact of one bony disk against the other. Unless we musicians are aware of using our spines well in sitting or standing, we tend to put tremendous pressure on the lower vertebrae, which is the most load-bearing part of the spine. The disks literally can be squeezed outwards causing pressure on important spinal nerves.

Figure 11: The Spinal Disk

In the Alexander Technique, we speak of the spine ‘lengthening’ in the sense that we look to stop the ways we habitually contract or shorten throughout the spine. How? One of the most common is by tightening the neck and pulling the head downwards. The spine will lengthen and the back will widen quite nicely, staying back where it belongs rather than pushing forward, IF the head is balancing in opposition Öforward and up.

Here are two contrasting pictures, one where the spine collapses and one where it is allowed to lengthen to sit:

Figure 12: Sitting in collapse (left) and sitting with poise (right).

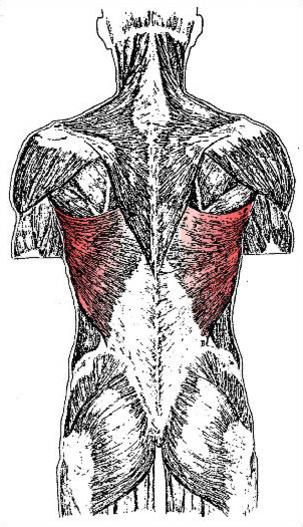

Let’s take a look at the powerful musculature of the back, primarily what Alexander called the ‘lifter muscles’, a.k.a. the latissimus dorsi. These muscles indicated below in red wrap around our back and make the job of lifting the arms easy, if we do not mis-use ourselves generally. They are literally our cello-playing muscles, providing the energy to take up our cellos as prepare to play, to maneuver the left hand and to push and pull the string with the bow. The Alexander Technique cultivates an acute awareness of the whole back through the practice of inhibition (stopping) and directing. In sitting and standing, the musculature of the back must lengthen and widen to provide the counterbalance to the weight of the head going forward and up. With long practice we eventually become more able to remember to leave the back quiet and not to thrust forward or narrow in preparation for movement. The back is the origin of our power, physical and emotional. It is not for nothing the expression: “He is the backbone of the team.”

Figure 13: The musculature of the back.

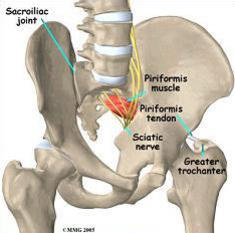

The Hips

The hip joints are important for cellists as we sit to play. The hip is a ball and socket joint with remarkable latitude of movement, made to open for a cello! Any holding in the hips compromises the free movement of the diaphragm (another story of connecting muscles) and therefore the breath; moreover we need freedom in the hip joints in order to accomplish weight transfer through the feetÖso that while playing our arms can be supported as they move away from the body and back.

Fig. 14: The juncture of spine and pelvis, showing the hip joint

Fig. 15: The hip joint and femur (leg bone)

The moment the knees go apart to receive the cello, the lower back usually pushes forward (or pulls back and down) and the hips tighten, drawing the top of the leg bone in towards the hip socket. It is almost an automatic gesture in cellists. Instead, we must learn to allow for the widening and releasing of the lower back so that the hips can rotate freely in the joint, and the knees can ‘grow away’ from the hips. All this, of course, while attending to the entire head-neck-back relationship, the key to our overall coordination. The hips will free up only in relation to the whole pattern of good use.

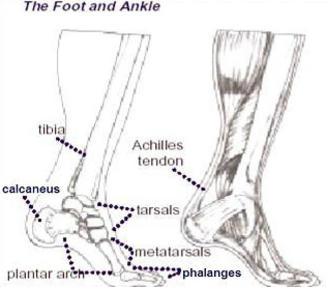

The Feet

Our feet are our foundation and tell their own story. It is fascinating to watch cellists’ feet on stage. They seem to have a life of their own. They shuffle, shift, slip and slide, go up, down and turn out sideways, they twist and arch and sometimes wrap themselves around a chair leg. They seem to act out movement for a tense body.

I see feet at one with their owner when I go to concerts of traditional musicians–African, Persian, or Caribbean. Their feet express the freedom of the whole self, in concert with the intention of the owner; they can be very quiet or they can lead the way. Whatever the ‘moves’, their feet are powerfully connected to the earth. It can be the same for cellists–in the films of Casals and Fournier, I can see these artists drawing their support from a well-grounded foot.

The foot is also a complex structure, with an arch which provides for spring, weight transference and shock absorption (see Fig.15). We gain an upward thrust throughout the body from the spring of the foot, provided we do not fix the muscles of the leg. The outward thrust of the knee is in relation to its base of support, the foot. “Knees over the toes, and that’s how it goes” is a rhyme I share with my youngest pupils.

Figure 16: The Foot and Ankle

I pay close attention to the feet of my pupils. They tell me whether their general coordination is working properly. I am not against the feet moving, but how they move is the question. Is it as a result of the general lengthening and widening taking place throughout the body or is it coming from unwanted contraction? A foot that is spreading onto the ground, with the heels well down and the toes lengthening away from the arch saysÖ I am ready to move.

And finally, the Chair Itself!

I know if I leave the chair out, you will feel left out. I will say little here as there are many excellent sources which discuss this issue [1]. The chair that is steady, sturdy, and of suitable height is adequate for our purposes. The question of height is important –the hips should not fall below the level of the knees. However, I have watched players misuse themselves on the finest ergonomically designed chairs. As one’s coordination improves, the chair assumes less importance (provided the seat is not inclined backward!) The long muscles of the back are extraordinarily powerful in maintaining our length, and good use encourages their development. Boredom, tedium and frustration are often at the root of pain, whether or not from long hours of work, causing one to contract or slump and to lose the upward flow along the spine. The Alexander Technique cultivates extraordinary power in the back which allows one to sit for long periods of time without tiring. Until such time as one can use oneself well, I recommend sitting with some form of support to the back and hips, if obliged to remain seated for a long time without the chance to move about.

The Catbird Seat

The practice of the Alexander Technique eventually leads to this knowledge— there is no way to sit correctly. Sitting well is not about finding a correct position and then holding onto it, contrary to our cello manuals. Sitting is dynamic, we move to make small (and not so small) adjustments to play. With practice of the Technique, we come to learn the principle of coordinated movementósitting is losing and regaining balance continuously, as is all movement. It is the capacity of our organism, when we do not interfere, to coordinate itself through the Primary Control—neck freeing, head forward and up of the spine, back lengthening and widening, knees forward and away from the hips as the feet take hold of the ground. Sitting ‘up’ is finding the catbird seat.

Figure 17: In Balance

Figure 18: Where’s my Cello??

ENDNOTES

1. Sazer, Victor. New Directions in Cello Playing: How to Make Cello Playing Easier and Play Without Pain, 3rd edition. Los Angeles: Ofnote, 2003.

Additional Resources

Latest News

- The Use of the Legs in Standing and Sitting May 9, 2020

- An Interview with Selma May 9, 2020

Copyright © 2021 The Well-Tempered Musician. All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy | Website Maintained by Nebulas Website Design.